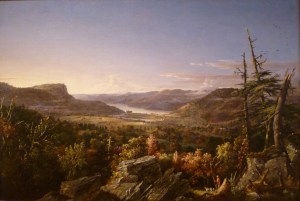

On our visit to the museums, we saw an exquisite plethora of paintings by the Hudson River School painters. This artist “fraternity” was started by Thomas Cole and continued to grow over the course of about eighty years.

In some ways, the Hudson River School became a response to “Manifest Destiny,” a belief filled with the hubris that white men literally had a God-given right and responsibility to control the land. At first, it inspired these artists and they tried to portray that concept. But as time passed, they became more and more aware of the true price of Manifest Destiny—how industrialization was polluting, ruining the land, and affecting Native Americans—and began to portray this in their paintings, sensitively leading the way as our nation’s first “environmentalists.” Watch for this as you look at the paintings below, ordered chronologically:

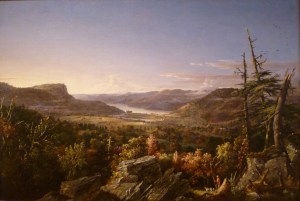

View Near the Village of Catskill, 1827, Thomas Cole (1801-48), oil on wood, , 24 ½ x 35

View of Greenwood Lake, New Jersey, 1845, Jasper Francis Cropsey (1823-1900), oil on canvas, 30 3/4 x 40 3/4

Boatmen on the Missouri, 1846, George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879), oil on canvas

“In the mid-19th century, the major western rivers of the United States served as interstate highways, with steamboats carrying both passengers and cargo. These steamboats were refueled on the river by “woodhawks,” men in small flatboats loaded with chopped firewood. Missourian George Caleb Bingham presented these boatmen as links between nature, represented by the wooded riverbank in the background, and civilization, symbolized by the advancing steamboat.”

“Bingham’s images of boatmen, now associated with the American Midwest, originally were considered railroad subjects because of their association with the frontier of pioneer settlement. Like the New England Yankee or the Western cowboy, Bingham’s Missouri boatmen were celebrated for their independence and helped to create both a regional and a national sense of identity. Bingham’s idealized depictions of boatmen as free laborers reflected his opposition to slavery and its extension into the western states.”

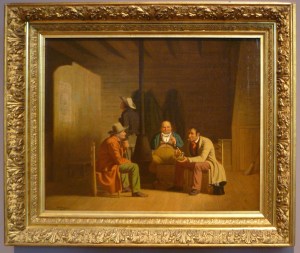

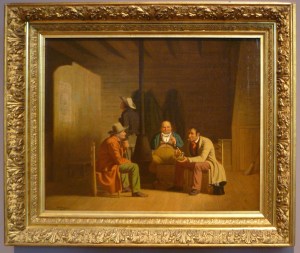

Country Politician, 1849, George Caleb Bingham, oil on canvas

“Country Politician, painted soon after George Caleb Bingham was elected a U.S. Congressman for Missouri, depicts American democracy in action. Seated near a stove, a young politician attempts to enlist the support of an older rural farmer, while a businessman–perhaps a local power broker–listens attentively. Bingham’s political subject would have resonated with his fellow Missourians, who participated in the intense debates about slavery that dominated American politics prior to the Civil War.”

“In 1849, the Missouri Senate passed the pro-slavery ‘Jackson Resolutions,’ which asserted that it was unconstitutional for Congress to limit slavery in its new territories. Bingham countered by introducing the ‘Bingham Resolutions,’ which recommended that the issue of slavery in the territories be decided at the state level. Country Politician promotes Bingham’s grassroots view that such difficult questions should be left to the ‘wisdom, intelligence and patriotism of the people of the entire Union.'”

The Arch of Octavius (Roman Fish Market), 1858, Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902), oil on canvas

“Ancient Rome’s Portico of Octavia, built by Emperor Augustus in 23 B.C.E., gradually fell into ruin and became a fish market in the 12th century. By the time Albert Bierstadt traveled to Italy in 1857, Rome was defined largely by its historical roles in the Roman Empire and the Italian Renaissance. It was also the most important destination for wealthy tourists who made the Grand Tour of Europe to view the roots of western civilization.”

“Americans such as the stoic man clutching his red Rome guidebook, accompanied by his wary wife, considered themselves the heirs of ancient Greek and Roman ideals, emulating their democracies and architecture. Yet Bierstadt’s painting documents the decline and fall of ancient Rome’s monuments, while two famous antique statues, the Sleeping Endymion and the Barberini Faun, are reincarnated in a sleeping man and the adjacent street sweeper. The fish-scale and scallop-shell frame motifs offer a playful pun on Bierstadt’s subject.”

At the same time Bierstadt was painting The Arch of Octavius, Asher Durand worked on his “River Landscape”:

A River Landscape, 1858, Asher Durand, oil on canvas, 32 x 48

Sunlight and Shadow, 1862, Albert Bierstadt, oil on canvas

“Albert Bierstadt’s view of the Gothic Revival chapel of the Löwenburg Royal Castle near Kassel, Germany, was based on an oil sketch he made in 1855 while a student at the Düsseldorf Academy. Given the religious subject, Bierstadt’s poetic title evokes associations with spiritual enlightenment and darkness. However, he also contrasts the man with a top hat inside the sunlit church with the impoverished woman nursing her infant, who serves as a traditional Christian symbol of charity but is cast in shadow on the steps outside.”

“The oak tree, a symbol of enduring faith in the face of adversity, and also of the cross, crucifixion, and resurrection of the Christian religion, was adopted as the national tree of Germany. Bierstadt incorporated oak branches and leaves into his custom-designed, Gothic Revival frame. This historical style, inspired by medieval precedents, sought to endow many machine-made, mass-produced goods of the industrial era with an aura of spiritual value.”

View of Donner Lake, California, 1871-72, Albert Bierstadt, oil on paper mounted on canvas

“Bierstadt made this study for a larger work that depicts a pass through the Sierra Mountains, several hundred feet above the Central Pacific Railroad.”

Nassau Harbor, ca. 1877, Albert Bierstadt, oil on paper mounted on paperboard

From the Getty Museum Placard: “THE HUDSON RIVER SCHOOL was not a school, but a group of artists who shared the goal of establishing an American landscape painting tradition independent from that of Europe. Despite nationalist motivations, Hudson River School artists were strongly influenced by European aesthetic concepts of the sublime (nature’s awesome power), the beautiful (harmonious and pleasing nature), the picturesque (nature softened by the hand of man), and association (the association of natural sites and human structures with historical events).”

“A sketching tour by Thomas Cole up the Hudson River to the Catskill Mountains in 1825 is usually considered to mark the beginning of the Hudson River School. New York City was the geographical center of the movement, which was also called the ‘native,’ ‘American,’ or ‘New York’ school. Although the artists traveled and worked in Europe, their favored subjects included the Hudson River region, as well as the Catskill, Adirondack, and White Mountains, and coastal New England.”

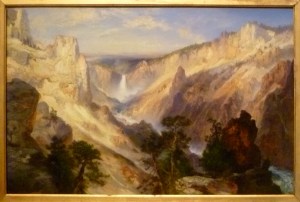

“Thomas Cole depicted the American landscape as a New World Eden that represented both god’s creation and the nation’s destiny to settle the “wilderness.” Frederic E. Church sought to evoke cosmic truths by blending art and science in large-scale landscapes. Martin Johnson Heade and Sanford Robinson Gifford created light-suffused landscapes that evoked a spiritual presence. Albert Bierstadt’s panoramic landscapes celebrated the grandeur of the American West and its suitability for settlement.”

“The decline of the Hudson River School style was brought about by the Civil War, which permanently altered Americans’ perceptions of their country and its contested landscape, by the growing popularity of European art among American critics and collectors, and by the fulfillment of America’s self-perceived Manifest Destiny to settle the entire continent, an accomplishment that reduced the American landscape’s rhetorical resonance.”

Orchid and Hummingbird, 1885, Martin Johnson Heade, oil on canvas

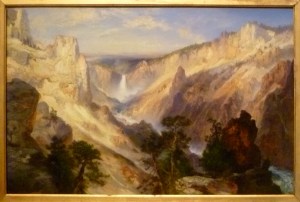

Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Wyoming, 1906, Thomas Moran (1837-1926), oil on canvas

Grand Canyon with Rainbow, 1912, Thomas Moran, oil on canvas

Note: All text in quotes is taken from the Getty or de Young museum placards posted beside paintings.

- A happy accident (timesunion.com)