There is a difference between instructors and teachers–instructors show you how, but teachers provide the “who, what, where, why,” and “how” of a subject. A teacher teaches you the theoretical aspects of the subject, helps you understand where you are going, why you’re going, and what to do when you get there. To me, that makes a tremendous difference.

All too often, I read articles by painters that parrot my teacher, Frank Covino, but fail to thank him for all they learned. Since I have been taught by him, I recognize his phraseology instantly. Well, to quote Frank, “It’s never too late to ameliorate,” so, as not to become one of those painters who forgets where they came from, I want to say that Frank’s giving, unselfish nature has truly been a gift I will forever cherish. I learned more about painting in my first week’s study with Frank Covino than I learned in all past workshops (that shall remain nameless), put together. What I learned from him way back then (and continue to learn) led me to see art and painting as truly a process and not a haphazard accident, with logic and a systematic method that removes the guesswork. This allows me to concentrate on creating and making fine-tuned judgments on value and color in my paintings. I will be always grateful to Frank for starting me on this path, as his dedication and striving for perfection in all aspects are inspirational and a great model to emulate. I wonder if he realizes how much so many of his students hold him in awe, and love and respect him for all the lives he has affected in such profound ways.

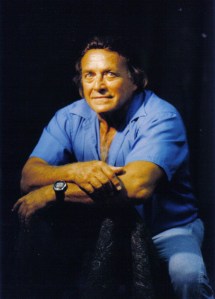

Photo of Frank Covino

Is there some kind of knowledge transference at birth? Perhaps there is, given that Frank Covino has been painting portraits since he was six years old. His mission: “To pass on the classical academic system of painting to the young so it doesn’t get lost.” This craft has been in the Covino family for centuries and, with over fifty years of teaching experience, Frank has made it his life’s work to impart the secrets of the Old Masters.

He reflects, “I teach because I was given an extraordinary, innate gift which revealed itself very early in my life. History has proven that the most extraordinary artists and musicians were also the best teachers and I like to think that I stand on the shoulders of those giants. Therefore, to exploit that gift would be a sacrilege. Thus, I will continue to teach as long as there are students who seek my guidance as it is my obligation to preserve this ancient tradition of my Italian ancestors.”

In this blog I’m writing, A Pigment of Your Imagination, I hope to pass on some of what I have learned as well.